Housing Finance Across Countries: Data and Analysis

While in high-income economies mortgages are widely available and routinely used for consumer financing of housing, many low and lower-middle-income countries only register a few thousand loans or a few hundred in some cases.

In the study of housing finance across countries, as an example, total mortgage debt outstanding in the Netherlands is equivalent to 83% of GDP, whereas it amounts to less than 1 percent of GDP across many low- and lower-middle-income countries in Asia and Africa.

What explains these differences? Are underdeveloped housing finance systems just a symptom of the general shallowness of financial systems across developing countries? Or are there country factors and policies that specifically explain underdeveloped mortgage markets? This paper uses new data to document cross-country variation in mortgage depth and penetration and explores country factors that can explain this variation and answer these questions.

Exploring mortgage finance and its determinants is important for both academics and policymakers. The maturity transformation of short-term liabilities into long-term assets, critical for long-term housing finance contracts, is also at the canter of financial intermediation theory, with many agency conflicts and market frictions even more obvious in mortgage finance than in other segments of the financial sector.

A mortgage loan is often the major liability of households in developed countries, with the house being the corresponding asset on the household balance sheet, and thus a critical part of household welfare. The importance and structure of mortgage finance is also critical for transmission channels of monetary policy.

Housing finance, however, has also been at the canter of multiple banking crises, most recently in the U.S., Ireland, and Spain, and recent research has shown that banking crises linked to housing boom and bust cycles are typically deeper than other crises (Claessens et al., 2011). Mortgage finance is also a critical segment of the policy agenda to “lengthen financial contracts” in many developing countries whose financial systems are dominated by short-term financial contracts and is at the centre of attempts to build up non[1]bank segments of the financial system (Beck et al., 2011).

Finally, the issue of housing finance can be seen in the context of a broader socio-economic development agenda. Many developing and emerging countries are still going through an urbanization process, which will increase the need for housing. Similarly, socio-demographic transition processes ongoing in many countries will increase the number of independent households and again increase demand for housing.

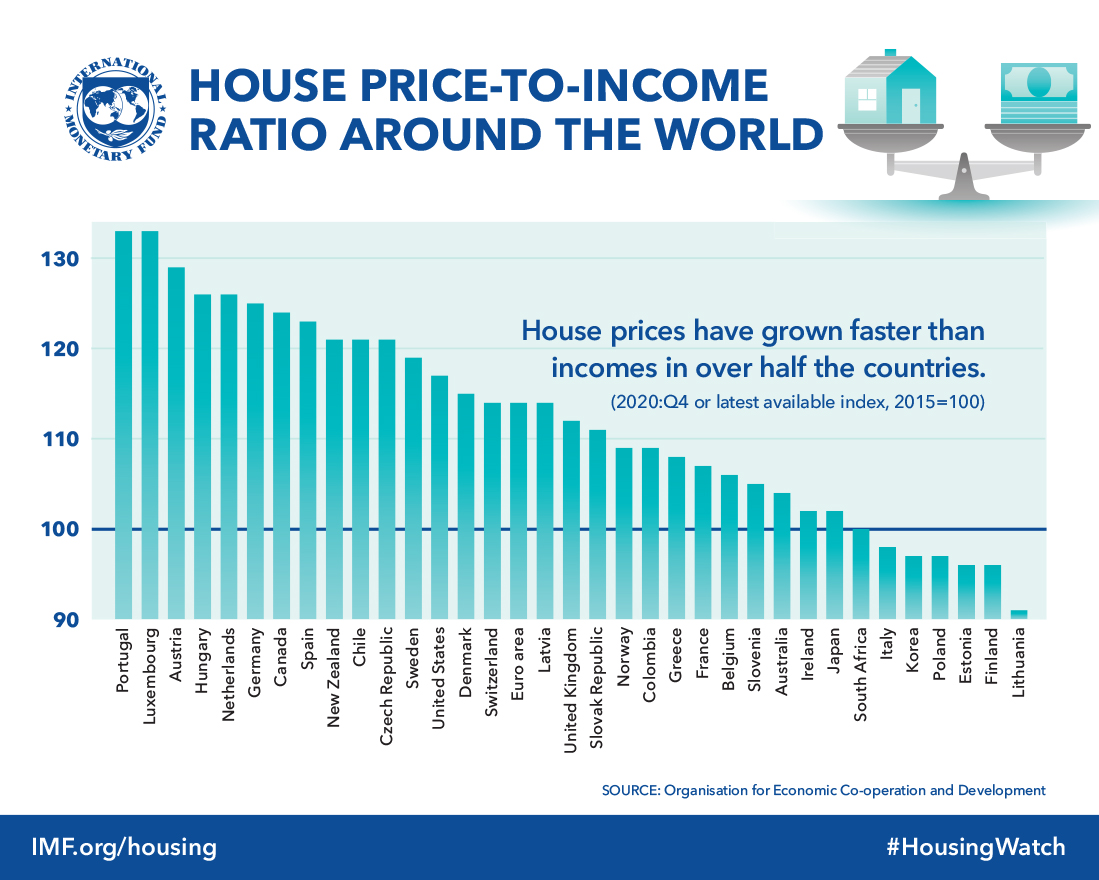

Additional housing, however, requires financing—as house prices are often a multiple of annual income—and mortgage finance systems in many developing countries currently do not satisfy the housing needs of these societies. Reforming mortgage finance systems requires the ability to understand, analyse, and diagnose their performance. While there is a long and extensive literature on housing finance across several developed economies, cross-country comparisons have been impeded by a dearth of data.