Overview of Slum Rehabilitation Schemes in Mumbai, India

The document provides an in-depth analysis of slum rehabilitation efforts in Mumbai, India, over the past decades, highlighting the evolution of policies, challenges, and outcomes.

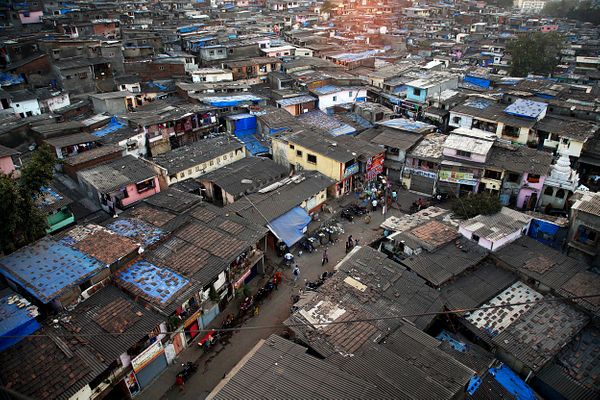

Historical Context and Urbanization

India’s rapid urbanization has caused severe housing crises, particularly in Mumbai. With a growing urban poor population—now forming 80% of the city’s population—slums emerged as a self-organized solution. Initial policies viewed slums as nuisances, prioritizing slum clearance without proper resettlement. These harsh approaches failed to resolve the issue, leading to recurring encroachments and further degradation of living conditions.

Initial Strategies (1971–1985)

The Slum Improvement Programme (SIP) in 1971 marked a shift toward improving living conditions rather than demolishing slums. The government provided utilities such as water and sanitation but faced financial and implementation challenges. By the 1980s, NGOs like SPARC began advocating for community-centered approaches, emphasizing self-reliance among slum dwellers.

In 1985, the Slum Upgrading Programme (SUP), funded by the World Bank, introduced tenure security and loans for slum improvements. This scheme sought to empower slum communities with affordable housing while avoiding heavy government subsidies. However, land acquisition hurdles and private land conflicts hindered its success.

The Prime Minister’s Grant Project (PMGP) of 1985 focused on Dharavi, offering subsidized loans for reconstruction. While innovative, PMGP was costly and only benefited a fraction of the population. High costs led many beneficiaries to sell their units, exposing flaws in cost recovery models.

Privatization of Slum Rehabilitation (1991–1995)

The liberalization of India’s economy in the 1990s triggered policy changes, enabling private sector involvement in slum rehabilitation. The Slum Redevelopment Scheme (SRD) in 1991 introduced an innovative cross-subsidy model, where developers received a higher Floor Space Index (FSI) in return for rehabilitating slum dwellers on-site. Additional FSI allowed developers to sell extra units at market prices to fund free housing for slum dwellers.

However, SRD faced execution challenges, including difficulties in securing consent from 75% of slum dwellers, temporary housing shortages, and developer mistrust. The imposed 25% profit cap for developers deterred major players, and eligibility criteria excluded newer slum dwellers.

The Slum Rehabilitation Scheme (SRS), launched in 1995 under the Shiv Sena government, built on SRD while addressing its shortcomings. SRS introduced Transferable Development Rights (TDR), which allowed developers to transfer surplus development rights to other parts of Mumbai. This attracted greater developer participation. SRS removed the 25% profit cap and abolished eligibility restrictions, extending benefits even to pavement dwellers. Despite innovations, execution remained slow, with only 26,000 households rehabilitated by 2002 out of a potential demand of 75,000.

Role of NGOs and Community Engagement

NGOs, particularly SPARC, the National Slum Dwellers Federation (NSDF), and Mahila Milan (collectively the “Alliance”), played critical roles in bridging the gap between developers, slum dwellers, and government agencies. They facilitated trust-building, consent collection, and project execution, particularly for infrastructure projects like the Mumbai Urban Transport Project (MUTP). SPARC’s efforts demonstrated the potential for community-led solutions, highlighting the importance of non-profit intermediaries.

Recent Developments and Challenges

The Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA), created in 1995, remains the central governing body for Mumbai’s slum redevelopment. However, progress has been slow, with only 197 of the 1,524 allocated projects completed. Recent court rulings aim to expedite projects by removing the 75% consent requirement for cluster development schemes.

Key Challenges and Lessons Learned

Mumbai’s rehabilitation efforts reveal critical challenges:

- Implementation Issues: Consent requirements, mistrust of developers, and inadequate temporary housing remain barriers.

- Land Value Conflicts: Developers prioritize upscale locations for profit, sidelining slums in less lucrative areas.

- Infrastructure Strain: Increased construction density risks overwhelming Mumbai’s fragile infrastructure.

The model, however, has introduced key innovations: deregulation of development controls, leveraging market forces for cross-subsidy, and NGO involvement. While criticized for favouring developers, SRS demonstrates a pragmatic approach to providing free housing in high-demand urban areas—a feat unattainable through direct government intervention alone.

Conclusion

Mumbai’s slum rehabilitation experience offers valuable lessons for urban policy worldwide. Balancing government facilitation, market participation, and community involvement is essential. The unique cross-subsidy model shows potential but requires better regulation, equitable distribution, and stronger infrastructure planning to ensure sustainable housing for the urban poor.

[PDF] Slum Rehabilitation Scheme, Maharashtra, India – View PDF ppp.worldbank

A case of slum rehabilitation housing in Mumbai, India – PubMed Central pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih